Maydi Newsletter: September

Dear readers,

Since our first issue in July 2024, the Maydi Newsletter has aimed to share knowledge, insights and stories that matter to our community. This month marks a new milestone: our first special edition, dedicated entirely to one theme, Somalia’s built environment.

Housing and infrastructure in Somalia carry the weight of history: the elegance of Islamic forms, the imprints of colonial rule, the scars of war and displacement, and now the pressures of rapid urbanisation and climate change. These forces have left Somalia’s cities both fragile and full of possibility.

To reflect on these challenges and chart pathways forward, we spoke with Bihi Mohamed, a Part 2 Architectural Designer whose thesis “Isku Tashi: Building Housing Capacity from the Ground Up in Somalia” argues that housing must be reimagined as a process rooted in skills, culture, and community, rather than an imported product. His words, threaded throughout this edition, offer both a diagnosis of Somalia’s housing crisis and a vision for building dignity and resilience from the ground up.

Somalia’s Built Environment Today

Somalia’s built environment tells a story of resilience and rupture. For centuries, Somali towns and cities were shaped by Islamic influences — courtyards, mosques, and shaded streets designed to bring communities together while responding to climate. Colonial rule left its imprint in villas, administrative buildings, and imported construction methods. War and displacement then fractured much of this fabric, replacing permanence with makeshift shelters, camps, and rapid, unplanned expansion.

At the same time, stark contrasts dominate the landscape. Villas and multi-storey apartments are built for wealthier residents and diaspora returnees, while just across the street, displaced families endure fragile, temporary structures that were never meant to last. With an estimated 300,000 people moving to cities every year, Somalia’s housing deficit is growing faster than it can be addressed.

Infrastructure has not kept pace. Public housing is almost non-existent, and urban planning frameworks remain weak. As a result, temporary solutions harden into permanent ones, leaving families in limbo — neither truly sheltered nor secure.

This is the backdrop against which architects, planners, and communities must work: a divided, rapidly urbanising environment where the majority struggle for dignity and safety in their homes. It is also the context that shaped Bihi Mohamed’s vision of “Isku Tashi” — a call for self-reliance, skills, and community-led housing capacity from the ground up.

Housing as Identity and Service

“Architecture has always been more than buildings. It is an integration of disciplines but most importantly for me an integration of identity, community, and service, a means of leaving something meaningful behind.”

Bihi traces this philosophy back to childhood. “Hooyo often reminds me of moments when, as a child of five or six, I would sit in class making cars out of cereal boxes. Later on I became fascinated with animated shows where I would draw and trace characters often. My parents then helped steer those small acts of making and drawing into a skill that could become a career they were familiar with, architecture.”

He remembers long drives with his father. “I admired skylines while riding in the back of Aabo’s taxi, and I became curious about Islamic art, architecture, and the idea of Sadaqah Jariyah, seeing design as a form of ongoing charity and service to people.” This layered view of design as service, as spirituality, as identity and it continues to shape his vision of housing in Somalia.

Isku Tashi: Self-Reliance as Resilience

The very title of Bihi’s thesis carries a message. “Isku Tashi means self-reliance, and that principle was the foundation of my work,” he explained.

Too often, Somalia’s housing depends on external actors. “Too often in Somalia we hear about foreign aid, imports, or outside professionals. While they provide relief, they can also create dependency, particularly in housing.” Instead, he believes resilience must be rooted in people and trades. “The climate can displace your temporary home, but it cannot take away your skills. That is where real resilience lies.”

For Bihi, this principle was reinforced by community examples. He pointed to “Aabo’s friend, Bashir Hassan, an immigrant to the UK who, through his savings as a bus driver, built an off-grid home in his hometown of Luuq while teaching others to do the same.” Bashir’s story showed how skills and knowledge, when shared, multiply resilience.

Somalia’s Housing Crisis: A Divided Landscape

Somalia’s current housing reflects deep inequality. As Bihi noted, “Villas built for diaspora and officials stand opposite millions living in buul, baac or corrugated shelters. The divide is stark, and what’s missing is affordable housing that provides dignity and stability for the majority.”

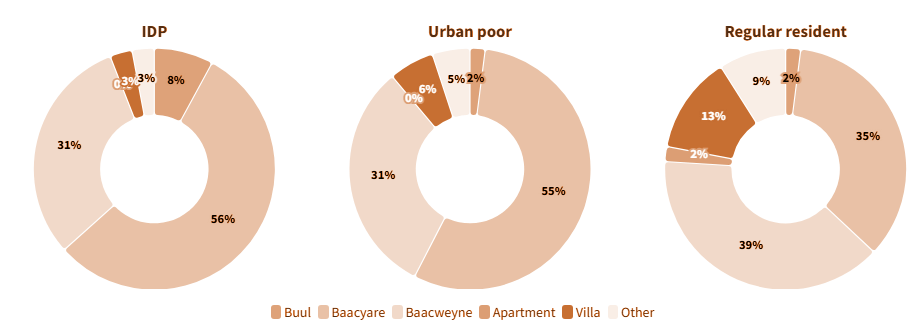

The data paints the picture: “Danwadaag data shows 56% of IDPs live in buul and 31% in baac, while the urban poor rely heavily on baac (55%) and baacweyne (31%). In contrast, regular residents are more likely to live in villas (39%) or apartments (13%).”

The numbers add up to a bleak reality. “UNDP estimates 72% of the urban population live in slum-like conditions… With 300,000 people moving to cities each year and almost no social housing being built, the deficit only grows.”

For Bihi, this is where justice comes in: “Housing justice in Somalia means moving beyond buul and baac towards homes that ensure safety, resilience and cultural dignity for all.”

Policy, Skills and the Role of Government

Public housing, in Bihi’s view, must begin with infrastructure and affordable frameworks. “Public housing does not need to mean fully finished homes for everyone, but it does mean creating affordable, safe, and permanent options for the majority, not just the wealthy few.”

The method matters as much as the outcome. “In Isku Tashi I instead of one-size-fits-all shelters looked at policies that could support incremental models such as Elemental’s ‘half-houses.’ These provide a framework and basic services while allowing families to expand, adapt, and personalise their homes over time.”

Participation, he stresses, is non-negotiable. “A key part of Isku Tashi was stressing participation, engaging people in design and construction rather than simply delivering ready-made solutions.”

But none of this is possible without tackling the skills gap. “My Aabo, who co-owns a cold storage fishing business, recently waited six weeks just to find a junior niche cold storage electrician. Similar to industry, the gap in construction trades is just as urgent. Investment in vocational training and apprenticeships is essential for improving housing quality, creating livelihoods, and reducing reliance on foreign labour or temporary aid.”

Empowering Communities

At the heart of Isku Tashi is community power. As Bihi told us, “For me, the clearest example is Aabo’s friend, Bashir Hassan… With that money he built an off-grid home, started farming, poultry, fishing and even beekeeping. What made his story powerful is that he also taught others to do the same so that the knowledge stayed in the community.”

Bashir’s words still resonate: “Meel kasta oo aan taabtay waxa ka dhashay nolol” (“everywhere I touched, life began”) and “Waddan kasta waxa dhisa dadkiisa” (“every country is built by its own people”).

For Bihi, even small actions matter. “Change can start small even from switching out a halogen light bulb for a LED lightbulb. I heartedly believe that positive change can be influenced using social media and networks, positive instances like Bashiir and the coverage of his positive actions can empower others.”

Tradition, Climate and Sustainable Design

Somalia’s climate vulnerabilities, Bihi argues, are also opportunities. “Solar energy is one of the clearest. With so much sunlight year-round, solar can provide households with consistent energy and reduce reliance on costly imports. This can power not only homes but also schools, clinics, and small businesses. Somalia also has access to strong coastal winds along its shores.”

He sees rich inspiration in heritage. “Somali and Islamic Sultane architectural traditions already provide inspiration for climate-resilient design… Passive ventilation with wind catcher towers, shaded courtyards, overhangs, and water features were used for centuries to create comfort and privacy.”

Examples already exist in the region. “A strong example outside Somalia but in and adjacent region with Somali people is the SOS Children’s Village in Djibouti, which applied these same principles with ventilation towers and shading while being culturally in touch.”

For modern solutions, he looks again to Somali roots. “Yes there are [traditional practices], with a lot of them focusing on shading, balconies, deeper reveals, and shading elements are central. They reduce solar gain while also being beautiful, like the Somali National Museum and its balcony designs.”

Nomadic traditions, too, remain relevant. “Nomadic forms of housing, usually lightweight, temporary, and moveable can carry lessons for today. They could inform better climate-responsive, temporary housing solutions for floods, droughts, or displacement.”

But the skills gap holds progress back. “Modern housing in Somalia remains limited in its forms and functions. That stems from a lack of construction expertise and engineering skills… That’s why skill education and training local professionals and workers is critical if we want to implement more vernacular, culturally sensitive designs into modern solutions.”

Envisioning Somali Cities in 50 Years

Asked to imagine the future, Bihi pointed to examples already built. “An example of design that draws directly from Somali culture is the Wave House by Omar Degan in Hargeisa… In doing so, it connects Somali and Islamic culture with modern sustainability.”

Nature, he added, should be central. “For us, the tree is a powerful metaphor. It is a place of gathering, of learning, of shelter… A tree is self-sustaining, efficient, and generous. Our houses should be like that, grounding us with central courtyards or green spaces and also our cities should be like that: alive, shading themselves, producing energy, and supporting community life.”

His long-term vision is bold. “Fifty years from now, an ideal Somali city would be renewable-dependent and self-sufficient, with a skilled local workforce no longer reliant on external forces… Cities would not only reflect Somali cultural vernacular but also act as ecosystems, just like a tree: rooted in place, efficient in function, and generous to its people.”

A Message to the Diaspora and Youth

Bihi closed with a personal reflection. “This is first a message to myself, as I’m still learning my own culture while trying to platform it. Create demand for Somali culture… Support heritage organisations too like Culture House in London or Somali Architecture (an organisation).”

Culture begins at home. “Once in a while put on the Dabqaad with some uunsi, get some decorative Somali patterns and support Somali creation.” And stewardship extends to the planet. “Be stewards of the earth. As Muslims it’s our duty: recycle, treat people and animals well, cut waste, use passive design instead of endless AC, and add solar to your homes. Every small choice counts.”

Finally, he stressed humility and collaboration. “If you’re involved in projects back home, drop pride and learn from locals. As diaspora we’re outsiders and respecting those on the ground makes architecture truly Somali. And for those at home, accept us, we need each other. This is isku Tashi.”

Housing is not only about having a roof overhead. It is where culture takes root, where service to others is lived out and where dignity can be restored. In his work, Bihi Mohamed shows us that Somalia’s future does not have to rest on dependency but can be shaped through our own skills, creativity and community spirit.

This special edition of the Maydi Newsletter is a tribute to that vision, a Somalia where homes and cities grow like trees, grounded in resilience, reaching upwards with hope and giving life for generations to come.

We thank Bihi Mohamed for sharing his insights, connect with Bihi on Linkedin.

Upcoming Events/News

🌎Be part of this evening’s event, empowering young people to connect global awareness with local action in the fight against the climate crisis.

🗓️Saturday, October 25 @ 2;00-4:00pm GMT + 1

📍Oxford House in Bethnal Green

🔗Registration link: [Sign up here]

ALSO ON AT THE SOMALI WEEK

🌎Join the discussion on Somali pastoralists and extreme weather by Hana, James and Martin. The session will highlight the importance of seasonal forecasting in the region and how better climate information can support pastoralist communities to adapt with resilience.

🗓️Monday, October 20 @ 6:00-7:30pm GMT + 1

📍Oxford House in Bethnal Green

🔗Registration link: [Sign up here]